Industry Rule No. 4080: Are Bad Record Deals Unethical, Or Just Part of the Game?

“Industry rule No. 4080: record company people are shady.”

A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip memorably sounded his warning about the perils of the music business almost thirty years ago; a cautioning that was well-reflected over the following years as news of multi-Platinum artists going bankrupt and global superstars changing their name a symbol to get out of their recording contracts became part of pop culture lore.

Stories of the entertainment industry have always been Little Red Riding Hood analogies: the young, vulnerable and overeager artists are seduced by the generous offerings of label execs dressed as friends and/or benevolent family figures. A look through any number of major music biopics (Straight Outta Compton, Why Do Fools Fall In Love, The New Edition Story), as well as VH1’s defunct Behind the Music and TVOne’s Unsung, will reveal stories of convoluted management deals and missing money, but also those of perfectly legal label and production contracts that didn’t match verbal promises. It’s why Ice Cube left N.W.A, why New Edition was only making dollars each at the end of their first tour, even according to some, possibly why Sam Cooke was murdered.

Last week, a conversation about fairness and ethics in record deals surfaced when first singer Kelis, then rapper Mase, called out what they consider injustices in their old contracts. In a Jan. 30 interview with The Guardian, Kelis said she was “blatantly lied to and tricked” by “the Neptunes and their management and their lawyers and all that stuff” when she signed her initial deal. The “Milkshake” singer says she was told “[we] were going to split the whole thing 33/33/33.” When she realized she wasn’t making any money off of her albums, only her touring, she says she questioned her deal. “Their argument is: ‘Well, you signed it.’ I’m like: ‘Yeah, I signed what I was told, and I was too young and too stupid to double-check it.’”

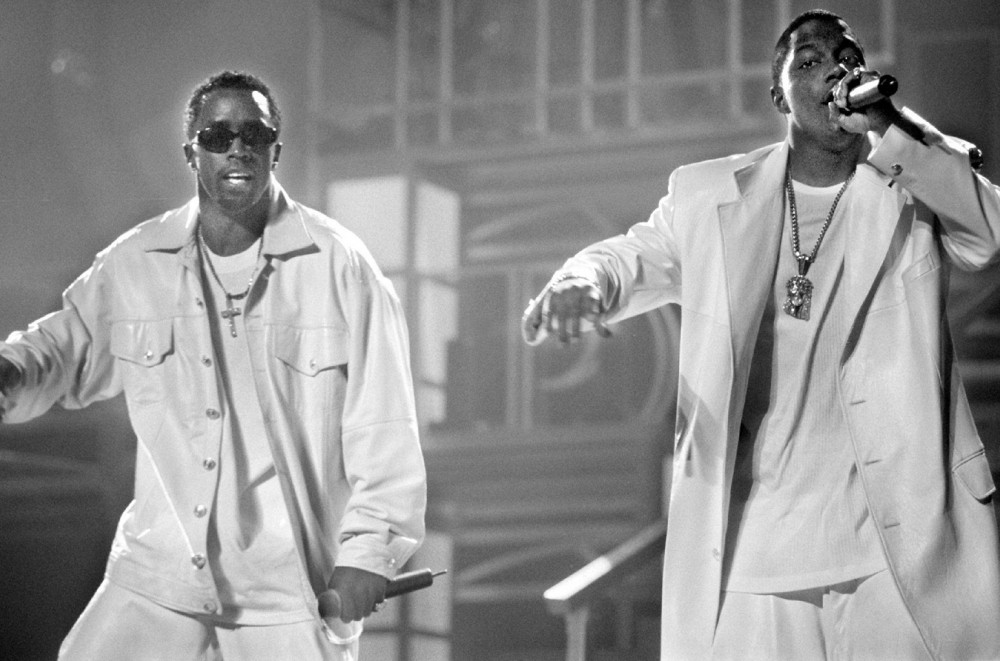

Kelis’ comments were followed a couple of days later by a post from Mase, once Bad Boy’s marquee artist and the new Starsky to Diddy’s Hutch following Biggie Smalls’ death in 1996, in response to an impassioned speech Combs delivered at Clive Davis’ pre-Grammy gala. While receiving the Icon Award, the entertainment mogul put the Grammy organization — a cosponsor of the event — on notice regarding their appreciation, respect and acknowledgement of Black artists, arguing “We need the artists to take back control, we need transparency, we need diversity.”

Diddy issued an edict on behalf of the Black music community for the Grammys to “get it right,” saying, “I’m here for the artists.” Combs also added that while his goal used to be simply making hit records, “Now it’s to ensure that the culture moves forward.” The magnanimous speech left Diddy, who now often uses the nickname “Brother Love,” open to criticism, as Bad Boy Entertainment has a trail of unhappy, messy or downright tragic artist relationships and breakups in its historic wake.

The Lox, Bad Boy’s rap trio from Yonkers, famously launched a “Free the Lox” campaign (that would have been such a great hashtag) in 2005, begging to be released from the label, going so far as to threaten Diddy on NY’s Hot 97. Among other claims, the group said the label head owned half of their publishing. Mase publicly addressed issues with his deal when making his return to rap in 2009. First, he confronted Diddy live on air during a 2009 radio interview, forcing him to sign a release that would allow him to work with other artists. A few years later, after Diddy blocked the rapper-turned-pastor-turned back rapper from signing with 50 Cent’s G Unit records, they finally came to an agreement that released Mase from his 16-year contract in 2012. At the time, Mase explained to MTV’s Sway the issues he had with his initial contract, including not getting paid for the iconic No Way Out tour. “You know how Puff is,” Mase told Sway. “I love him, but you’re gonna cut your arm off to get free.”

Since 2012, the two seemed to have made amends; Mase joined the Bad Boy reunion tour, and even performed in tribute to his former collaborator at Davis’ party. But somewhere between that event on Jan 24th and Friday Jan 31st, Mase apparently approached Combs about buying back his publishing — which he claims Diddy paid him $20,000 for in 1996 — for $2 million. He says Combs declined. For a little math: Harlem World sold almost 5 million records, and Mase is rumored to have written at least some of Combs’ parts on the No Way Out album, which has sold more than 7 million records. Even without knowing exact numbers, we can assume Mase would have earned exponentially more than $20,000 had he retained his publishing rights. Mase accused Diddy of being unfair to the same artists that helped earn him the Icon award, and of “screaming ‘Black excellence’” while doing business in bad faith.

While both Mase and Kelis’ stories feel cut and dry, it’s hard to officially weigh in without having access to the deal terms and paperwork, and without knowing who received what legal advice. Artists are sometimes persuaded to skip legal counsel, or are referred to their lawyers by the same “friends” they’re doing business with, who may not take the time to make sure they understand everything. Also, contracts can be confusing for a non-legal executive who works in the business, even more so for a teenager with no knowledge of contracts or the industry. Lots of numbers and language someone new to the game may not know; and all too often have not felt they needed to know beyond the figure for their album advance — until the first big expected check was not as big as they anticipated. Then, they learn: about recoupment, producer fees, sample clearance fees, and publishing royalties.

There have been major artists caught in deals that were flat out illegal. Boy band impresario Lou Pearlman was sued by his artists the Backstreet Boys and *NSYNC for fraud stemming from convoluted contracts, meant to siphon money in ways like naming himself as a band member, retaining ownership of the band name, and claiming exorbitant costs from developing the group. From 1993 to 1998, Backstreet claimed they only saw $300,000 while Pealman made $10M.

And then there’s legal — even standard — but unfair. Berry Gordy had a template that more than one JV later followed: artists were signed to Motown or one of its subsidiary labels, and to Motown’s management arm International Talent Management, and signed to Motown’s Jobete publishing. Not illegal, just a lot of different ways the company is getting paid before the artist does. Diddy managed his Hitmen producers, signed his artists to his own publishing company, and was credited as an engineer, mixer, producer, songwriter and executive producer on most albums. But he wasn’t the only label head who did business that way.

In Kelis’ case, the “33/33/33” promise is confusing: Kelis says both that she didn’t make any money from her first two albums, and that Pharrell “stole” her publishing. Kelis only co-wrote three songs on her debut album, Kaleidoscope. Chad Hugo and Pharrell Williams wrote the rest, were getting paid as producers, getting extra points as executive producers, and were also featured artists on the album as NERD. Kelis co-wrote a majority of her sophomore album, Wanderland, but the project wasn’t released in the U.S. until 2009 due to conflict with her label, Virgin. Even without knowing the details of publishing splits or how her label was paying her, it would have been difficult to construct an equation in which the Neptunes didn’t receive the lion’s share of both royalties and back-end money, so an even three-way split was unrealistic. But the details of recoupment, songwriting splits, and multiple roles the Neptunes were being paid for may not have been sufficiently explained to Kelis.

In best case scenarios, if an artist has a terrible deal initially, they gain the leverage after a successful debut to renegotiate better terms or even to leave for another label (as *NSYNC did for No Strings Attached — get the title now?). Worst case, they’re stuck fighting for their creative and financial freedom indefinitely. (See: The Artist Formerly Known As Prince). In the cases of Kelis and Mase, Mase successfully renegotiated before his sophomore effort Double Up, but then left New York — and the business — without even promoting the project. Kelis signed to the Neptunes’ Star Trak label for 2003’s Tasty, her most successful LP to date, but she notably only mentioned her first two albums in her interview, so perhaps she felt that deal was equitable.

In the last decade, the rise of digital music has helped level the playing field; artists are more informed, more empowered, and don’t automatically look to labels deals as their first option. They can create a fan base, build an audience and even tour while remaining self-contained, and come to the table with their own terms when time to consider a larger partnership. And contrary to some current schools of thought, major labels are still relevant if you need radio budgets and infrastructure.

Ultimately, though, the music business is a business, with stakeholders and bottom lines (even Combs and Bad Boy were accountable to parent company Arista Records). Part of the outrage on behalf of both Kelis and Mase is that they were played by people who are supposed to be friends — family even. Unfortunately, there’s not a hard and fast answer on where the line is between giving someone a chance and protecting your investment, and taking advantage of someone who doesn’t know better. So kids, watch your back: Industry Rule No. 4080 will in some way be in effect as long as there’s an industry.