31 Years Ago: Rage Against the Machine Release Their First Album

Applying the politics of Rage Against the Machine’s debut album to today’s current climate, it’s obvious the world has not changed like the Los Angeles rebels had hoped. The iconic line, “Some of those that work forces / Are the same that burn crosses” can now caption the polo-clad, tiki-torch wielding white supremacists that marched in the streets of Charlottesville in 2017. The scope of today’s political rage was essentially foretold throughout Rage Against the Machine’s 1992 debut.

Rage Against the Machine were born from the bones of the members’ former projects. Zack de la Rocha was fronting hardcore band Inside Out, while Tom Morello was jamming in the funk-metal band Lock Up. Lock Up’s drummer Jon Knox would convince Tim Commerford and de la Rocha to play with Tom Morello, as he was looking to start a new band. With the help of Brad Wilk, they formed what would become Rage Against the Machine, a name taken from a planned album for Inside Out.

Rage Against the Machine, “Freedom”

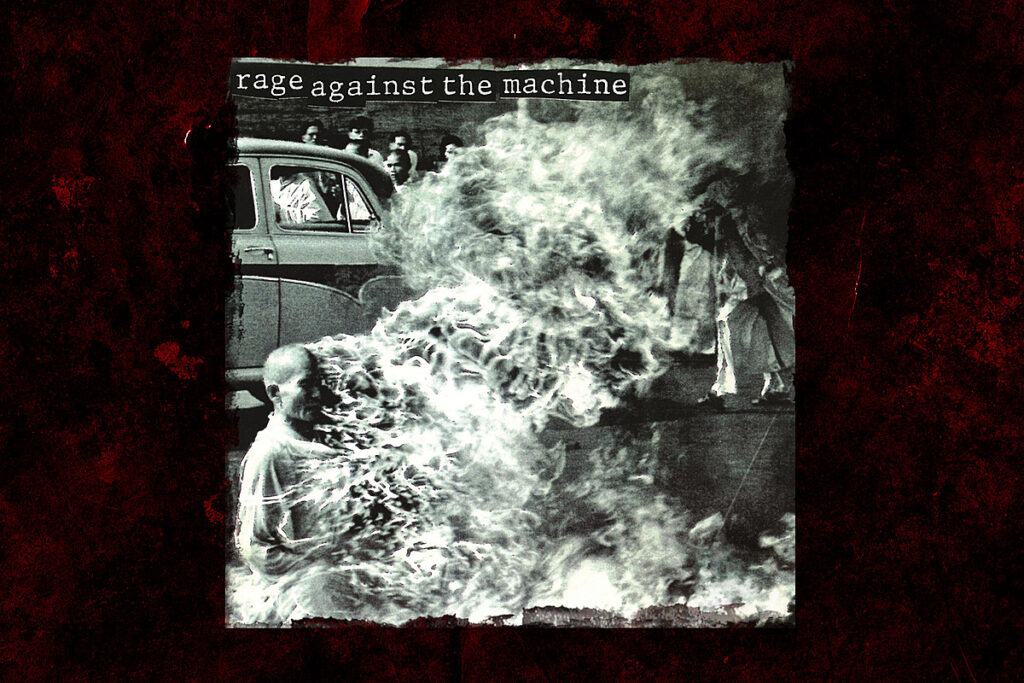

The self-titled Rage Against the Machine was developed from the band’s original twelve-song self-released cassette tape. That demo featured clippings from stock market newspaper reports meshed together with their band name on top and a single match taped to its center. The self-titled album is an expansion of that theme, using an image of Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức setting himself on fire in protest against his government. His immolation is Rage’s politics made real: sacrificing every bit of yourself in order to express what’s right.

With rap rock at a fever pitch and bands forming hollow versions of what Red Hot Chili Peppers honed into, Rage Against the Machine took the rhythm and groove of hip-hop and merged it with the kind of funk Morello keyed in on with Lock Up.

Rage Against the Machine, “Bombtrack”

Album opener “Bombtrack” is as incendiary as its title would suggest, with Zack de la Rocha’s lyrics twisting rap braggadocio and evoking as much aggression as possible, introducing himself with a guttural “ughh!” Fire remains a constant throughout the track, setting up in the listener’s head that what you’re listening to is without a doubt something dangerous, perhaps even a weapon.

The beauty of Rage’s politics is an ability to take complicated, controversial issues like police brutality against black men, distill the pure anger felt from reading about it, and transforming it into song. “Killing in the Name” has become one of the band’s signature tracks for this reason. Musically, the members create a push-pull, start and stop dynamic early on. Building up to a groove, the riffs sound as though one side is fighting the other before resolving with silence.

Rage Against the Machine, “Killing in the Name”

Repetition becomes the key to the song, as only about eight different lines are uttered in the song’s five-minute run time. There’s a weight to everything, de la Rocha’s vocals blurring the line between rapping, screaming and singing. Morello’s riffs cruise through like a tank, their funky heaviness creating a tone so specific it would solidify him as one of rock music’s most memorable players.

As the song hits full ignition, Morello and company turn their instruments into noisy static while Zack quietly repeats “Fuck you I won’t do what you tell me,” until he hits a ballistic fever pitch. In a single song, the band blended punk’s ethics and attitude with heavy metal’s metallic and brooding textures to create something infinitely compelling for listeners.

The rest of the album builds on those two songs, showing the band iterating their style of music in interesting and exciting ways. “Know Your Enemy” (which features Tool’s Maynard James Keenan) shows de la Rocha both telling his own story and asking listeners to take up his call to arms, aimed at the system and its false cultural narrative of the “American Dream.” Instead, he suggests the “American Dream” taught to him at a young age was really a way to keep him unaware of the realities around him and that violence is an everyday fact of America. He ends the song singing out “All of which are American dreams!” with more and more anger and despair in his voice as the song ends.

Throughout the rest of the album, Morello defines his guitar sound with “Fistful of Steel” setting his guitar tone somewhere between a police siren and a woman screaming, before winding up in a wild solo of wah-wahs and guitar screeches at its end. The rest of the band hold the line nicely as well, Wilk’s drumming becoming tribal at times and Commerford’s low-end treading heavy and cool.

Each member takes their time in their playing and songs like “Township Rebellion” allow each member to sit back and riff things out in a powerful and confident way. Rage Against the Machine plays out like one singular piece, one song able to reference a previous cut through de la Rocha’s lyrics or in the group’s instrumentals.

Thanks to some high profile slots on tours like Lollapalooza and opening for Suicidal Tendencies, Rage Against the Machine connected with all kinds of people feeling disenfranchised throughout the world. Early reviews were drawn to the band’s confidence in their playing, unafraid of how people may take either their politics or genre mixing. The album would go on to sell over three million records in the United States, certifying it triple platinum.

At face value, the group’s music can be overly simplified to adolescent rage against a teacher or parent, but digging into the lyrics offers the listener a reward of being able to learn about different struggles as told by the band. Their songs would go onto inspire some less virtuosic bands, unable to critically think about where their rebellion is coming from or who it’s directed towards. But Rage Against the Machine did inspire real awareness for fans of rock who might not have expected it, turning music into something weaponized and palpable.